How we built a marketplace that was self-sustaining and scalable, by representing stakeholders in code and aligning their incentives.

Hrishi Olickel

Published on 27th Sep 2019

16 minutes read

(Note: The cover image is a colony of Volvox, an algae that forms little clusters of multiple organisms into one superorganism. They're stunning, and if you're not sure how it relates to physical security do read on.)

The world of physical security is one I've had to explain many times over the last few months. It's an interesting one - I started working on a company that provides a marketplace service for physical security some time ago. While I was initially expecting a standard marketplace, it quickly became clear that there were open technological problems in this space we needed to solve. This post explains some of our solutions at the level of architecture and data. I'm hoping to do a deep dive on the development work later, but this is a big enough task on its own. I might split it into two, I'm not sure. If you'd like to skip the introduction, go to What is a transaction.

In very simple terms - so we can start with the problem - physical security is the 'physical' side of security. The security that comes to mind for most people these days is cyber security, especially if you live in a developed country. Cyber is what dominates the news cycle, and with good reason - compared to most other forms of security, the effort and personnel needed to mount a cyber attack is tiny, triflingly so when compared to the payoff. The DAO Hacker made away with over $150 million USD, worth even more during the market's peak, and yet the hack was something that could potentially be accomplished with a single attackers' time, little money and a few weeks worth of concerted effort. With the world moving to open networks, protecting them becomes ever more important, even if it might be sisyphean.

So it's understandable that we forget that the world we live in has to be guarded by men with guns, and it's more often than we think. Physical attacks are ever present and need physical security - armed men and women, vessels and transports - to defend against them. It's out of sight and out of mind for many of us, but it is a constant concern and expenditure for the governments and corporations of the world. I wish I could tell you different, but I can't. Physical security today is a $150 billion USD market, and it has problems. For an industry concerned with protecting human life, it has problems it really shouldn't.

I'm hoping this will serve as a short introduction to what the purpose of the work we do is. I'll elaborate at length on the problems of the security market some other time. For now let's boil the biggest concerns down to keeping out bad actors, ensuring good performance and - I hate that this is true but it might even be one of the biggest - cutting down the paperwork. Moving on, I'll try and keep the analogies and examples as general as possible but this should help with understanding.

In the simplest terms, the function of a marketplace is to connect buyers and sellers. In the physical world, that's sometimes as simple as announcing a location and a time where the two can congregate and talk to each other. It's not very different in the virtual world, where the primary function is asset and price discovery. Can you find the products you want? If so, can you make a decision on which product to buy?

Modern marketplaces have added another layer on top - managing the transaction. It turns out that one of the biggest hurdles in any marketplace is getting the two sides to trust each other - and this is a lot higher for an online marketplace than a physical one. If I look back to my first transaction on eBay, I had the same concerns. What if I press this button and nothing shows up? What can I do? In the physical world we rely on social pressure. the environment and non-verbal interaction to comfort us. Looks like a good guy, there's a lot of people around, others are buying things from him, and this doesn't look like a shady place. Online marketplaces have had to try and replicate the same things in order to complete the transaction, and they're perfectly positioned (not that perfectly, but pretty good) to be the middleman. Performing escrows, buyer reviews and buy counts, guaranteed return schemes, etc. all serve to replicate similar functions we find when doing a transaction in the real world.

Online marketplaces soon added another layer - services. If you're buying a shirt, use OUR augmented reality tool to customise your fit. If you're selling a shirt, use our inventory management system. Thus, the SaaS-enabled marketplace was born. This was sometimes a product of necessity. The speed of transaction and availability that the internet brought with it meant marketplaces quickly infringed on each others' business. The behavior of the modern buyer differed from the old in their need for fast completion - the first page of search engine links get all the traffic, the first page of market results get most of the transactions, and so on. Leakage became a problem. A marketplace works best for the consumer when it's a monopoly, same as any other platform for aggregation. If I need to subscribe to twenty streaming platforms to be sure I can watch what I'd like, the experience suffers. In high-value marketplaces, especially ones where the same customer was likely to use the same supplier for the same product over again, the chance of leakage increased. This occurs even in marketplaces where supplier and product churn was expected to be high - I've been asked many times by Uber and OLA drivers to simply call them directly the next time I wanted an airport pickup, and offered to split the applications' cut.

If I remembered to, I definitely did. This was because once I had met the driver, the platform had exceeded most of its usefulness to me. It had (somewhat) vetted the driver and helped us find each other. I didn't need it the next time I needed the exact same service. To get around this problem, the new breed of SaaS-enabled marketplaces provided features to buyer and seller to increase lock-in. It's an effective model if used correctly.

All this is the roundabout way of saying that we decided to build a marketplace, and our knowledge of the market led to a SaaS-enabled one. Now we get to the interesting bit.

This is where the complication starts. Physical security from the outside looks like a simple marketplace. Buyers want to procure security for some reason - they have a ship going through a high risk area that needs an escort, they have a production crew or construction team going into a country they don't know and they'd like armed protection. Sellers (or suppliers) have these services available and want to find buyers. Both have some price in mind, there's some negotiation and eventually they come to an agreement. The demand and supply look decently uniform (and they are in the general sense), and price and asset discovery are major pain points in the industry.

The problem is that physical security is not one big market. It's a lot of smaller markets that have evolved on their own, often isolated from each other. Think garage sales before online auctions, but with a lot more at stake when things go wrong. The markets are separated by geography, type of service, duration and many more things. Suppliers often operate within locked verticals. Clients pay multiple middlemen for their rolodexes to access different verticals. Unified price and asset discovery is alien to this world.

This is also a problem for us, and it becomes a bigger one due to the complexity of a transaction. In a standard e-commerce platform, the transaction - from an agreement between buyer and seller to successful delivery of the product - is simple by comparison. The product is sent, the service performed and the seller marks it as such and the payment is released in the case of escrow. In our market, multiple levels of agreement have to be reached, documents provided and verified by both buyer and seller, progress monitored closely (often over multiple days) before the transaction is complete. This is further complicated - and sometimes rightly so - by the amount of oversight required. The cargo owners of a chartered vessel may need to conduct their own due diligence into the security being provided, and multiple regulatory agencies around the world may need to be satisfied by it's depth. The transactions look very different from vertical to vertical, despite similar supply and demand. This is not taking into account that security is often a three-sided agreement. Contractors perform the work on the ground, suppliers hire out contractors and the clients purchase that service. Multi-party consent and involvement is part of the story.

As it well should be. This is an industry tasked with protecting lives, involving men and women with deadly pieces of machinery, and millions of dollars worth of equipment and people that need protection, which makes it a problem worth solving.

Before we dive into the specifics, let's look at the things we need to accomplish. We need a platform that can unify the market across verticals while capturing the business process and logic specific to each vertical. We need to make adequate provisions for external oversight, and build in methods for excluding bad actors. Oh, and we need it to scale. Even the comparatively simple process of figuring out the exact data schema for a transaction (there's no unified format even in a single vertical) for a market that hasn't seen a lot of technology, and iteratively optimizing it until both parties are satisfied is a task that doesn't scale. The work required on the platform side to induct and manage each new vertical is constant, and ideally we'd like it not to be.

The first step for us was to take multi-party consent out of the equation and solve the data problem first. Figuring out the roadmap is just as important as the platform itself, to find out how to layer the solutions we introduce. Once we solve the problem of schema and the connection between verticals, we aim to tackle consensus. We have some plans on how to do this, and I'm silently praying we're not rebuilding raft. Greenspun's tenth rule comes to mind.

The next step is to separate the information we need to deal with into high level components that are generalizable across all verticals and strip out all the pieces that aren't essential. In all the verticals, there is an asset (a service or a product) that is being provided - that needs description. There is also always an engagement - the structure for what information needs to be exchanged when and in which format, which needs to be described. The asset is described by the asset schema, which outlines the data spec for describing the thing that is being sold. The engagement is described by the contract, which outlines the data, but also encodes a time component. Some information is exchanged before others, and some information is required before the transaction can move forward. We also have at least two party consent to work with, so that needs to be part of the schema. Agreement needs to also be encoded into the engagement.

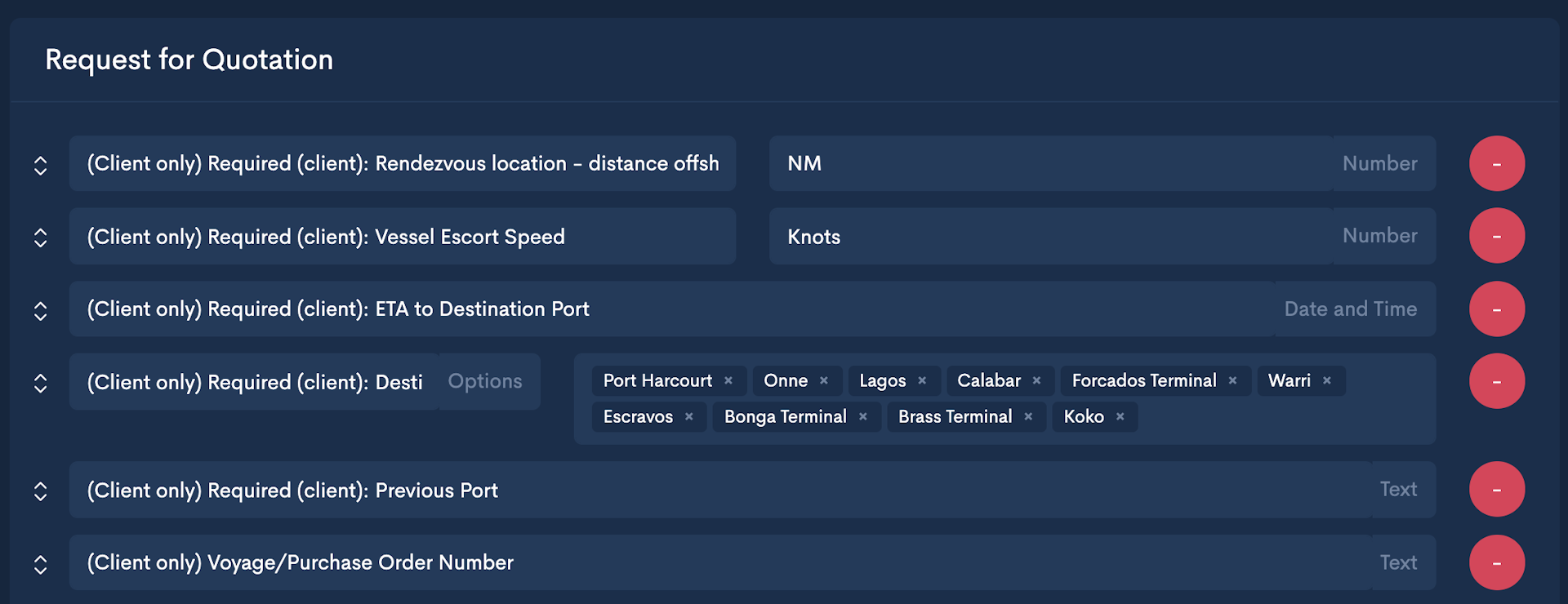

To encode this information, we split the contract into phases. Each phase needs to have consent from both parties - buyer and seller - before proceeding to the next one, so consent is implicity encoded in the progress of the engagement. This also allows us to split what is otherwise a complex data structure into eccentric and oft-used parts. The often used parts we can add additional support for and tighter integration, like a Request for Quotation (RFQ) and a Quote (Q? I'm just kidding).

With this in mind, let's look at an example.

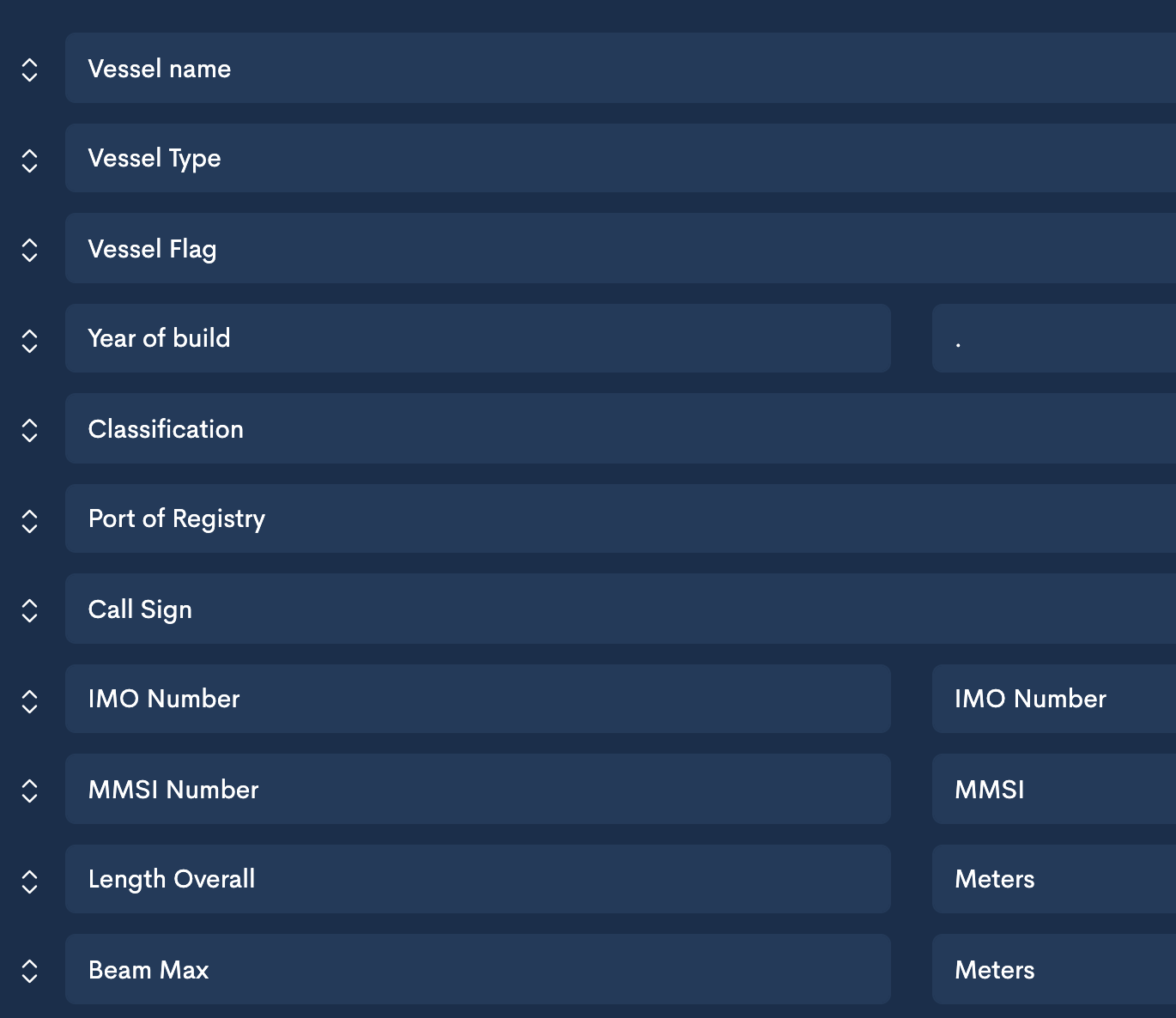

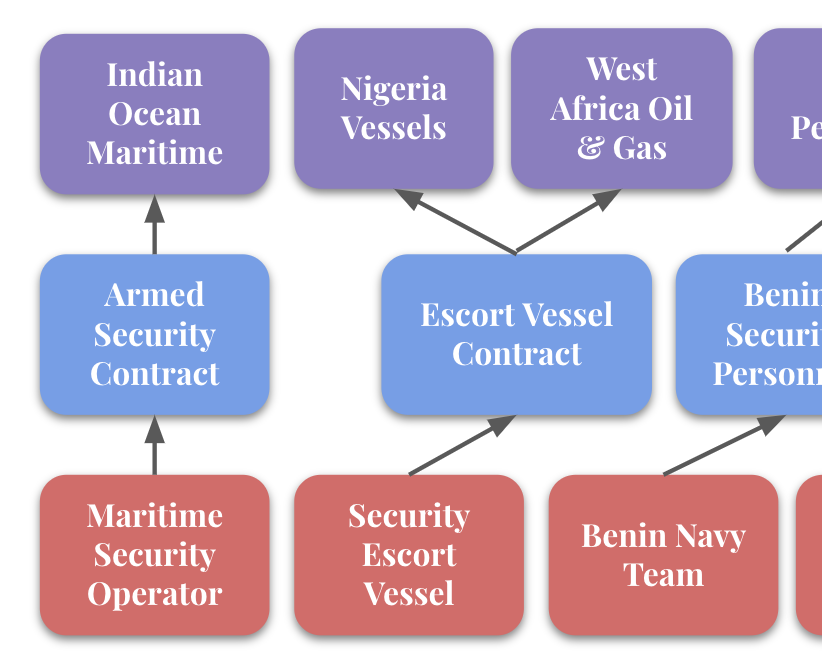

I'd like to procure an escort vessel for a ship transiting through a high risk area near Nigeria. First, I need to know what the escort vessel is, and it's described by a specific schema.

This schema is largely unchanged regardless of the service provided. The service-specific information, like location and additional regulatory data is encoded in the engagement. So for Nigeria, we use a specific contract:

We can now start seeing how this works. The asset schema is the what, the contract is the how.

The final piece in this system is the where. That's where the market comes in. A market is a simple position marker. It's the interface for clients to congregate, so they can find what they're looking for. In a standard marketplace, this is simply a property of the asset - pants, shoes, dresses. You don't necessarily need to (or even when you do, there's no difference in process to) sell the same exact pants in Africa and Europe. Here, the market denotes the vertical that clients congregate in. Escort vessels in Nigeria? Close protection in Europe? Different markets, with different deployable assets, each with a different contract.

This is how we put them together. Markets provide points for clients to begin, asset schemas points for suppliers to onboard. Contracts connect the two, and an engagement can exist when all three are present. In the ideal sense, a client can go to the relevant market and immediately find suppliers and assets that fulfill that need. A supplier can onboard an asset to the right type and be instantly connected to all relevant markets.

This is how the data is structured, and it solves the problem of capturing this data and ensuring a transaction can complete online. A UI can be built around the concept, and we can start.

It still doesn't solve the problem of scalability. The solution to this is to bring in a new type of user, what we've taken to calling the intermediary. Once the schema is separated from the data itself, and we've allowed for mechanisms to finely encode time and consent into the specification, we can allow others to build their own. To see how this works, let's consider the process of adding a new vertical, perhaps in response to a new spike in demand.

Security moves in boom cycles, as new high risk areas are created. 9/11 did that for airport security, and pirates in 2002 did that for maritime security in the Indian Ocean. Let's imagine that tomorrow, new outside investment flows into a high risk area, creating new demand for security for construction projects, flights in and out, and risk assessments. With this system, an outsider with some knowledge of the market - perhaps someone holding a position on the sell or buy side - can identify relevant assets that can be deployed. If none exist, they create a new asset specification, which is then connected to a new market via a contract. Under our system, we can monitor the ownership and use of contracts. For each engagement that is executed based on the contract, the intermediary is compensated some percentage.

This provides an incentive for the intermediary to optimize the contract so as to attract buyers and sellers, as well as onboard them to the system. The intermediary is the focal point for that contract, accepting feedback about missing fields, problems with the current spec, updating to improve the engagements going through it. This also encourages competition at the data level, where multiple intermediaries can create their own contracts if the existing solutions aren't good enough, incentivized to find new and niche use cases and to support them. Once a market matures, the platform can integrate the contracts and provide a better flow for the user.

This aggregation of market knowledge allows the platform to scale past what the company and the team behind it can accomplish alone. Competition is regulated and the number of middlemen substantially reduced, with the intermediary providing a useful service to both buyer and seller.

If this sounds complicated, it is because it works to serve this vision. Supply and demand are generally uniform across the verticals in physical security, but mobility is hugely restricted preventing useful migration of personnel to where they're most needed and valued. Being a singular store of data across verticals helps track bad actors through the system, where currently reports of misbehavior are born and die in small company data siloes. Visibility will help this market, where inflated prices and low contractor pay are common, and this is what we hope to do.

Which brings us to the last problem we'll discuss here. An astute reader will note that this system encourages asset and engagement schema duplication. If a similar enough asset exists but not the exact one you need, an intermediary has no option but to create a new one, forcing suppliers to duplicate their inventory and onboard the same assets again. Similarly, multiple contracts from intermediaries for the same service will cause buyer confusion.

To solve this we implement two concepts often repeated in OOP - Inheritance and Polymorphism. I'm borrowing the names because they fit best, and the ideas only at the high levels. Inheritance applies to assets. A base asset schema - for vessels or personnel - is created from which additional attributes can be added to create a new one. All existing assets of that type qualify as the new type once the supplier completes the difference. For example, a contractor for close protection may have his general background, certificates etc. For a specialized market where female guards with specific experience are preferred, an inherited asset can be created to suit the needs of that vertical, with the additional required fields added in.

For contracts, we mentioned identifying common phases before. Connecting contracts at the phase level with polymorphic properties provides a solution here. For example, a client can fill in an RFQ once, without needing to choose a contract, and contracts that the filled in fields are applicable to will be activated. This provides a uniform interface to both clients and suppliers, and a well tuned version of this system can abstract away a complex data management in the background.

Putting the two last pieces on this system, we can start considering the possibility of a global security marketplace - a digital security marketplace that allows free movement of personnel and services, instant price and asset discovery, oh and the ability to manage the engagement across multiple actors. Let's save that for another post.

There are a few more problems we've outlined but not described the solutions to: cutting down paperwork and easing the process of due diligence, allowing regulatory oversight, and multi-party consent. I'll cover those in a separate post, before going into detail on the implementation.

(About the algae. I hope the analogy of an organism, that lives in locked clusters for most of it's life and then finds a way to escape and form new associations to suit the environment, make an interesting parallel.)

We release every week.

Learn about new tech in maritime, and what we've built as soon as it's live.